Jack White has never been one for doing things the conventional way. Whether it’s taking his wife’s surname during his first marriage, creating bills using crayons during his brief time in the upholstery business, opening up his own record store in a bid to save physical media, or starving himself for five days while writing Entering Heaven Alive, he’s always been the kind of guy to walk to the beat of his own drum. When you also consider his incredible discography musically - across The White Stripes, The Raconteurs, The Dead Weather, and his six solo records - normal is a word that can’t really be applied to Johnny Guitar.

So I guess when White turned the traditional album and touring cycle on its head earlier this year, I shouldn’t have been so surprised. But when I think about what the biggest music story from the past year is, there aren’t many examples that surpass the innovation, genius, and straight up coolness of what Jack White did with his latest release, No Name - which is one of, if not the top record put out this calendar year.

At this point, most album promotions roll out in an almost identical fashion. An artist will announce a new single to build anticipation ahead of the release date for their new record. If there’s an accompanying tour, those dates will be announced closer to the album’s release date. A dozen presales are announced for the tour. Pre-order information for 5-to-10 color variants of the album are marketed. Spotify asks you if you want to pre-save the record. Additional singles are dropped as the release date draws closer. It’s a tried and true formula to keep fans and listeners in perpetual waiting, increasing the hype until the album is unfurled or they find a leak online, the latter of which is becoming increasingly rare these days.

That is, of course, unless the artist gives it away for free and encourages fans to share it on the internet – which is exactly what Jack White did on July 19, 2024. Customers making purchases at his three Third Man Records locations in Nashville, London, and his hometown, Detroit, found an added bonus in their record bags that day – a record labeled No Name in an otherwise unmarked record sleeve.

Unsuspecting vinyl enthusiasts quickly discovered that this was not only just unreleased Jack White material, but in fact a completely new album that had been released without a peep of promotion. Word quickly spread across the internet about No Name, spurred on by a local Detroit station playing the album in full, and the official Instagram account of Third Man Records displaying a picture of the album with the phrase “RIP IT,” seemingly encouraging fans lucky enough to receive a copy to pirate and share the new songs – which they did en masse.

White’s not the first artist to release a completely free album to his fans – Radiohead, Nine Inch Nails, and U2, amongst others have done so digitally. He may be the most famous, however, to give away a physical copy, and is certainly in the small class of artists who would encourage the taboo illegal piracy of his own work. To do so in this day and age, where artists increasingly have to rely on physical media sales, touring, merchandise, and other revenue sources in order to accommodate the pittances they receive from streaming, is borderline insane. But whereas an up-and-coming band might balk at such a strategy, the well-established White could take a chance on something so bold – and it paid off handsomely.

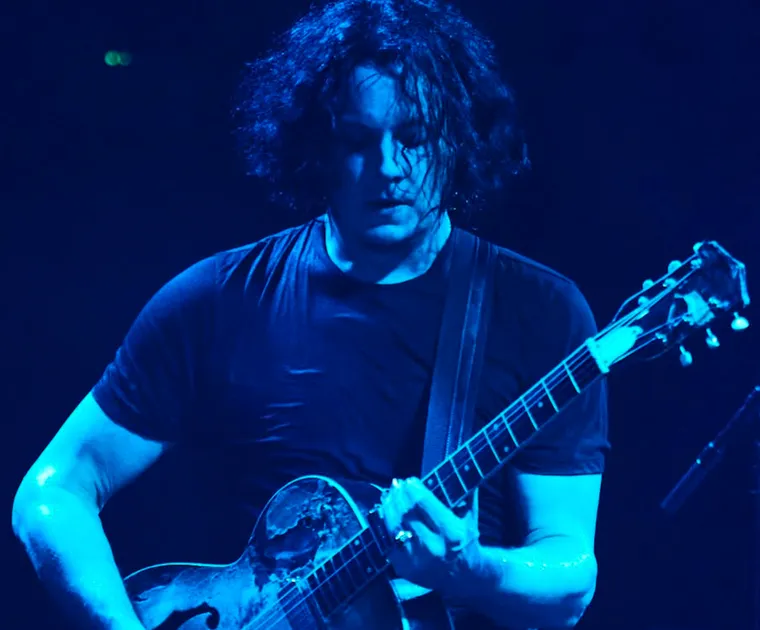

For the first time that I can remember in quite some time, there was a palpable buzz surrounding a record’s actual release. As bootleg rips of No Name circulated the internet, fans dissected each track, giving them names so they could be discussed, and lauded the album as one of White’s crowning achievements in his career. Their praise was not hyperbole – No Name is the rawest, most impassioned collection of songs Jack has put together since his days in The White Stripes. You would be hard pressed to find a weak link on No Name, which does harken back to his days with ex-wife Meg on drums. There are several standout tracks on the album, but none which serve this discussion better than “Archbishop Harold Holmes,” which might be my favorite rock song written in the last five to ten years. It also serves as the blueprint for the next phase of marketing No Name and the subsequent tour White would embark on.

Written and performed as a letter from the aforementioned Archbishop with just enough televangelist huckster delivery, White implores his congregation to follow his recommendations to achieve self-fulfillment with a level of bravado I haven’t seen from him, perhaps ever. And these recommendations, are essentially to go see him play live. Take the first verse, for example:

Dear friend

If you want to feel better

Don't let the devil make you toss this letter

If you've been crossed up by hoodoo voodoo

The wizard or the lizard

You got family trouble? Man trouble? Woman trouble?

No light through the rubble?

You're looking for a true friend or a true lover

Or if you've been living undercover

I'm coming to your town to break it all down

And help you with all of this

I'm looking to help you find bliss

One day, one way, can't miss!

It’s hard to explain, but as he’s done in the past, White essentially adopted the persona of Archbishop Harold Holmes as an alter ego for this album and tour cycle. The letter he’s writing could easily be applied to going to see Jack White perform live, implying that it’s as spiritually fulfilling as getting right with the Lord. (Ironically, White was going to enter the seminary in his teenage years before learning he couldn't bring his amp with him). He’s also telling you flat out that he’s not going to do it the usual way:

I'm here to tear all the walls down

Doesn't matter if it's a large town or a small town

Just like Joshua and the fabled walls of Jericho

I'm here to tear down the institution

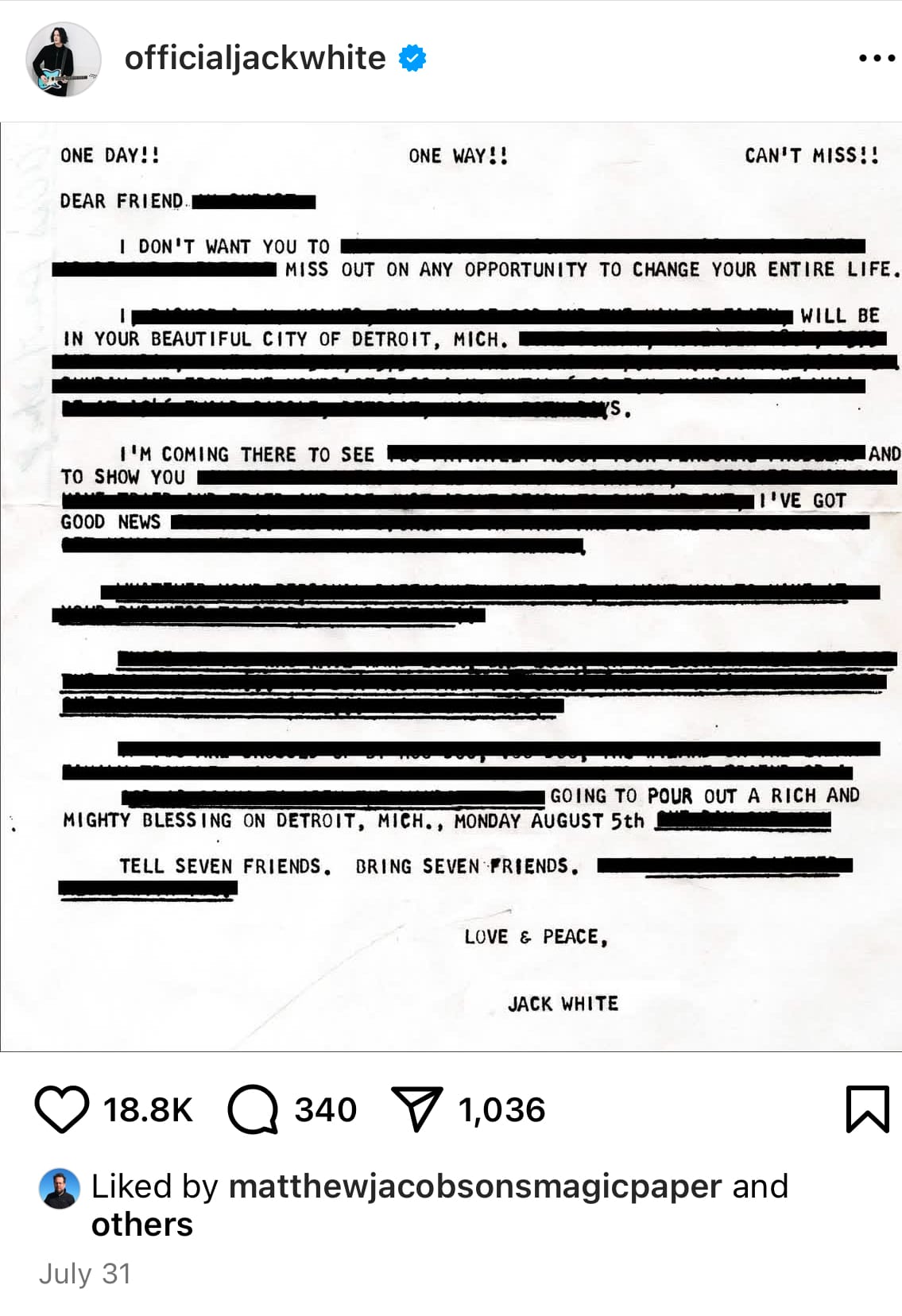

So, given this pretext, we have to look at what A.H.H. did next to fully understand how prophetic the fifth song on No Name was to what would be coming for Jack White fans. Shortly after the relatively unmarked records were given out at Third Man, White announced a benefit show in Nashville that would take place on July 31st at a relatively small venue about a week before it would happen. The next day, he announced two shows in Atlanta, again at small venues, with about two days notice. On July 29th, he announced another Atlanta show on the same day that it would occur. Fans flooded online ticket markets to get tickets for the shows, which would take place at venues that hold approximately 500 people, at maximum.

Again, message boards and subreddits were afire with comments about these popup shows White was playing. Surely, this was just a promotional stunt to build on the buzz already generated from the underground release of his new album. But, then he added a show in his hometown of Detroit on August 5th, with tickets selling out in minutes with a little more than five days notice.

In the midst of these shows and the frenzy to get tickets, White announced the proper release of No Name on August 1st. The album would be released the next day, but only at Third Man Records. Fans had a chance to preorder one color variant and one regular black edition for about 24 hours prior to its proper release. Those who missed out had to wait months for their hometown record store to even acquire a copy – I know because I called mine once a week to see if they had it.

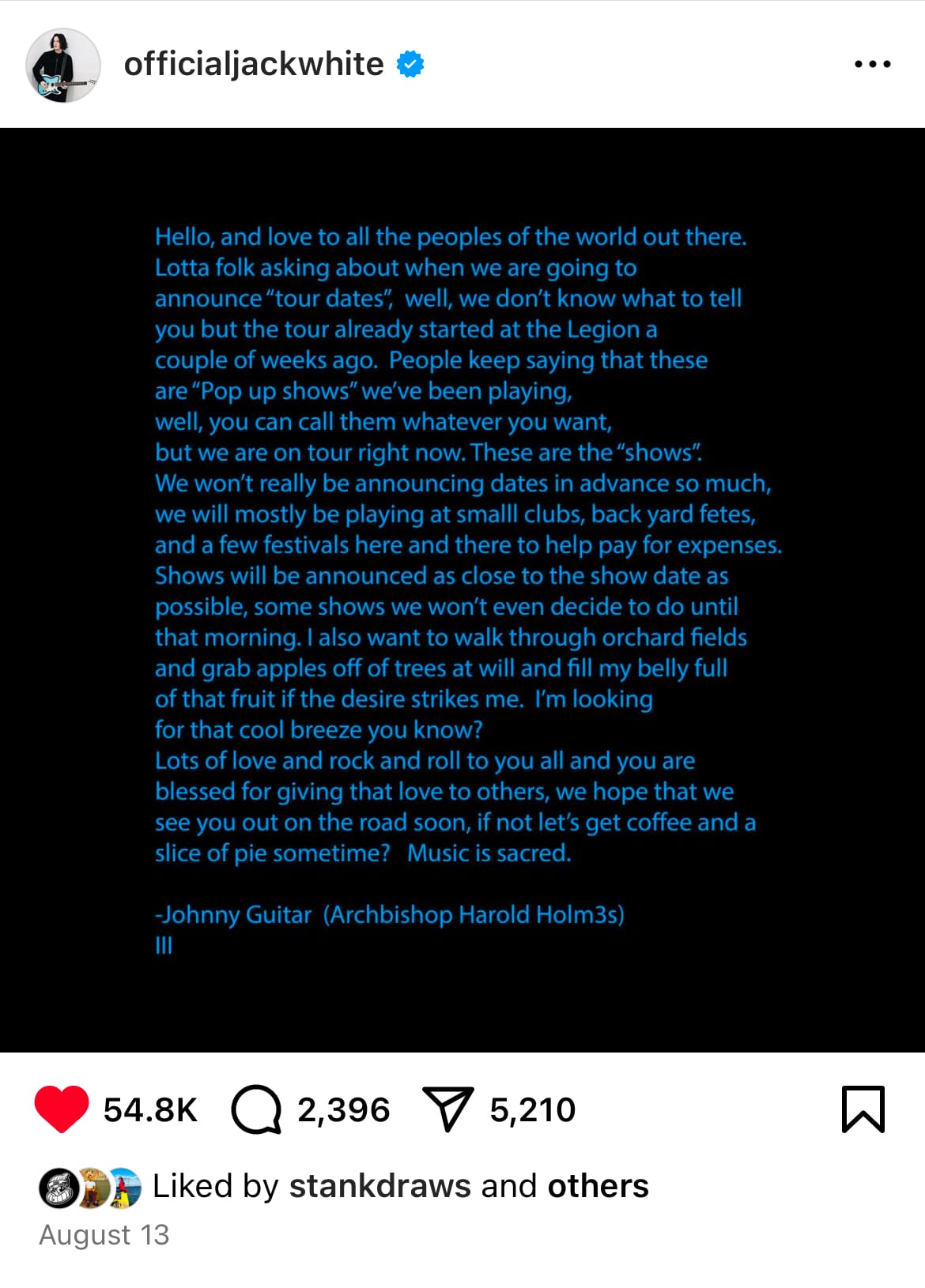

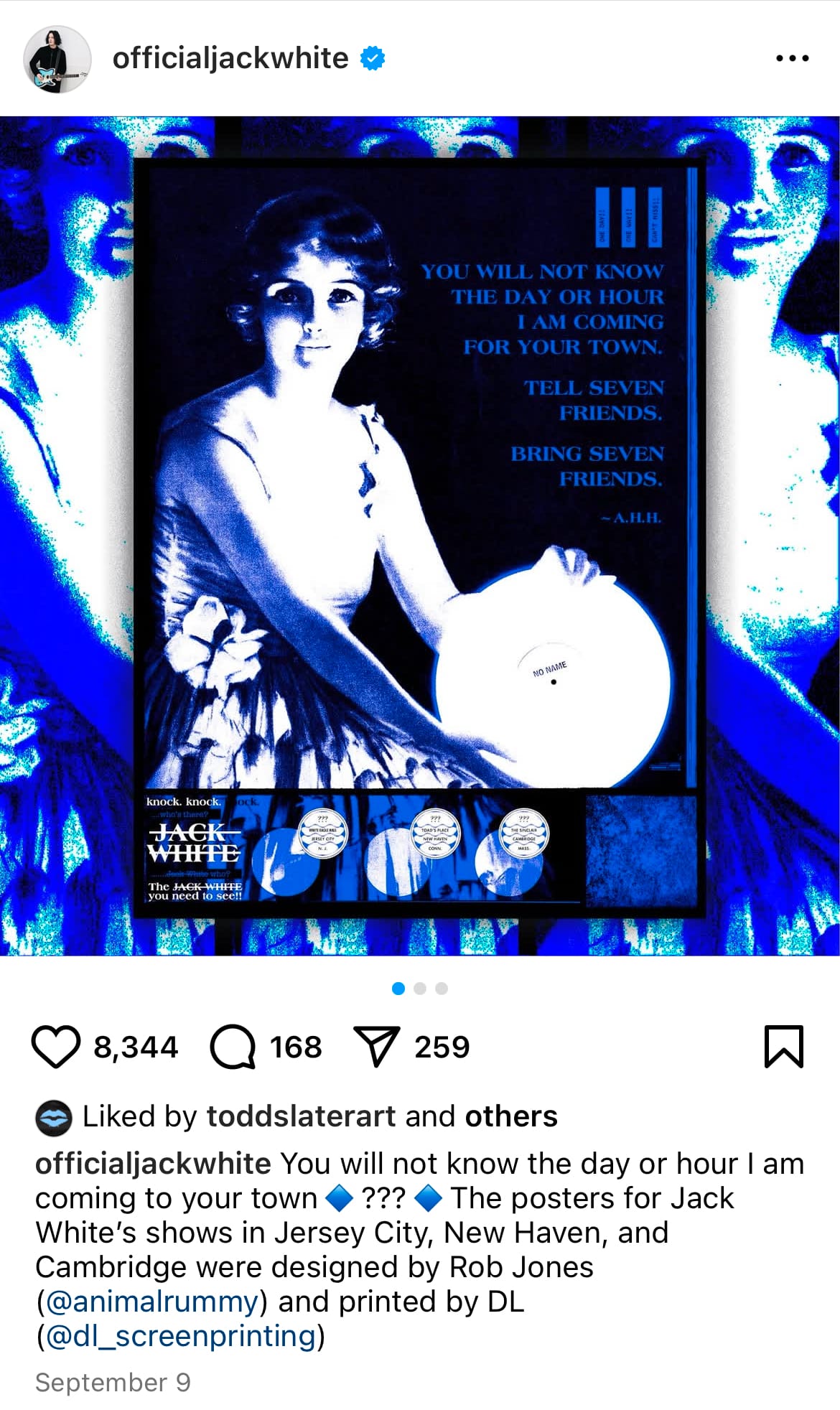

Meanwhile, the shows across the United States with little to no notice to purchase tickets continued. After likely being inundated with questions from fans about when A.H.H. was coming to “their town,” White issued this message on Instagram to his fans feverishly trying to see him perform.

The poster art for his shows even bore a quote suggesting the nature of the tour, with a quote from the Archbishop saying, “You will not know the day or hour I am coming to your town.”

That proved to be true, as White continued from September through November to play randomly announced shows throughout the United States, usually with a day or so's notice. Sometimes, however, fans would be notified the morning of a show. In one of the more absurd turns to this story, White played two shows in Austin in one day, one being an 11:30am matinee that fans had perhaps three hours of notice in order to acquire tickets, bang out from work, and attend the show.

If you’ve listened to the song, you might be asking, “What about that big money blessing that Jack White said he’d give me if I came to see him live?”

Open up the windows of heaven

And pour out a rich and mighty blessing

Not on his town, or her town, but your town

Are you ready for the message?

I have a special financial blessing that once I have placed in your hand

Then I want you to begin using this blessing on the very first day that you can

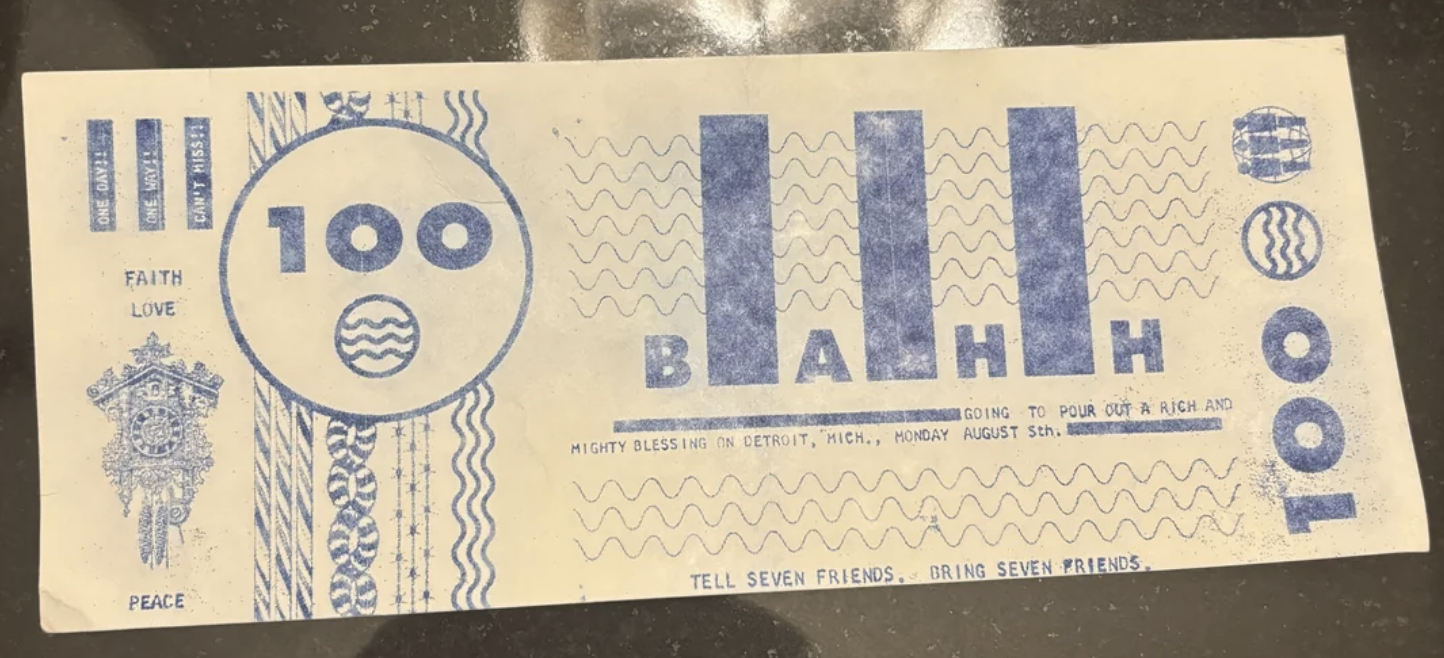

Well, have no fear – many concert attendees reported receiving these bills from the Bank of Archbishop Harold Holmes seen below – though their purpose to this day still seems unclear.

Some claim they can be redeemed at Third Man Records in the future, while others who were less patient have sold them on eBay for upwards of $1,000.

In the midst of this madness, as a fan of Jack White, I was forced to be tuned in to all of his social media, specifically Instagram, as that was the most immediate way to be notified of an upcoming show. I failed miserably trying to get tickets for his three NYC adjacent performances, but was suckered in to buying festival tickets when he was announced to replace Foo Fighters at Surfside in Bridgeport. Given the information that I had, that this is the tour and this is how it’s going to be announced, I figured it was my one and only shot to see him perform all these new songs I loved so much. I then proceeded to drive to a festival on a Sunday night out of state, which is very out of character for my concert-going behavior. The marketing strategy worked perfectly on me, and yes, I am a sucker.

Because after the surprise show announcements subsided midway through November, Jack White finally showed some conformity to the norm: he announced a 51-date, multi-continent tour on November 18th which would feature him playing at more traditional venues. And of course, those shows sold out almost immediately.

Let me say first that I am no master of economics. But the brilliance of playing small venues with little to no advanced notice creates an incredible demand for a product that can never be fulfilled with the supply of 500 tickets. However, now that you’ve created that demand, which in turn has people painfully paying attention to every move you make, those once spurned fans who missed out are now eager to pay to see what they missed out on the first time around. Obviously, the product needs to be worthwhile, and Jack White has proven time and time again with every live performance he’s done, that it is.

The same logic can be applied to his handling of the release of No Name. Limit the supply of the physical media, both with the in-store giveaways and the formal release of the record, slow play the availability of it around the world, therefore creating an incredible demand for it. The strategy landed him in the Top 10 for Album Sales on Billboard during the week of No Name’s release, alongside the likes of Kanye West and Taylor Swift.

In both aspects, it’s simply brilliant.

The guerilla marketing of No Name, the brilliance of “Archbishop Harold Holmes” as a song and a tour strategy, and the way he was able to create such a high demand for his live shows are just another example of the genius and innovation of Jack White. Surely, he has a strong PR team that was involved, but at its core, this feels like his idea. If you were a fan of his in 2024, you had no choice but to pay attention to his every move for hopes of receiving the “rich and mighty blessing” of seeing him perform live, or securing a copy of his new record. More so than any of these things, the strength of No Name as an album and the marketing behind it injected a bonafide rock ‘n roll artist back to the top of the charts, which is becoming a more rare feat with each passing year. For all of these reasons, Jack White’s accomplishments this year should be lauded and exalted – and perhaps, imitated by other rock artists seeking relevance in this day and age.